12.7 History of tropical cyclone flooding

Three recent tropical cyclones producing catastrophic flooding include Hurricane Harvey (2017), Hurricane Florence (2018), and Tropical Storm Imelda (2019). Four historic tropical cyclones, Hurricane Agnes (1972), Tropical Storm Albert (1994), Tropical Storm Allison (2001), and Hurricane Irene (2011), caused inland flooding events.

Agnes

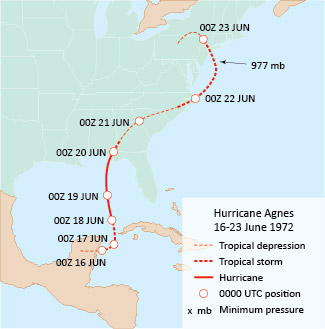

In June 1972, rains from the remnants of Hurricane Agnes accounted for much of the storm’s nearly $12.9 billion (2019 dollars) in property damage. Agnes tracked up the Eastern Seaboard from southwest of the Florida Keys to North Carolina and then northward into Pennsylvania (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The track of Hurricane Agnes in June 1972. This relatively weak system brought flooding rains from Virginia north to New England. [NOAA data]

The storm brought beneficial rains to the Southeast, which had been experiencing a dry spell, but heavy rains in the mid-Atlantic were anything but beneficial. During the week prior to Agnes’ arrival, frontal showers and thunderstorms produced soaking rains from Virginia to New England. Rainfall averaged 3–8 cm (1– 3 in.) and locally topped 15 cm (6 in.). Agnes’ torrential rains fell on saturated soils, producing runoff that triggered many record-breaking river crests and devastating floods.

The heaviest rains from Agnes fell in a band about 350 km (215 mi.) wide from western North Carolina northeastward into central New York State. While rainfall totals were variable in the hilly terrain, they ranged from 20–30 cm (8–12 in.) during 18–25 June. Some localities reported total rainfall in excess of 46 cm (18 in.) with more than 25 cm (10 in.) falling in only 24 hrs (Figure 2).

Flooding was particularly severe in central Pennsylvania where rising waters forced more than 250,000 people from their homes. The Susquehanna River crested at 4–5.5 m (13–18 ft.) above flood stage. Of the 122 fatalities attributed to Agnes, 50 were in Pennsylvania, and flood damage in that state accounted for almost two-thirds of total storm damage.

Alberto

The first tropical storm of the 1994 season, Alberto never achieved hurricane status yet its rains took a terrible toll in a band from southeastern Alabama to central Georgia. Alberto developed in the western Caribbean Sea and strengthened to a tropical storm on 1 July. After drifting slowly west-northwestward, Alberto turned north and, on the morning of 3 July, came ashore near Fort Walton Beach, FL with peak sustained wind speeds near 97 km per hr (60 mph). The storm then weakened rapidly as it drifted across southeastern Alabama and into central Georgia.

Alberto likely would have received little notoriety except that its moisture-rich remnants slowly meandered over central Georgia and eastern Alabama for three days. Many local weather stations reported 3-day (3–5 July) rainfall totals in excess of 25 cm (10 in.), with a maximum storm total of 54.8 cm (21.6 in.). Alberto’s torrential rains caused rivers to rise to record high crests, and flooding was extensive. The Ocmulgee River at Macon, GA broke its old record by 1.7 m (5.5 ft.) when it crested at more than 5.2 m (17 ft.) above flood stage. Most of the storm’s 32 fatalities were victims of floodwaters. Property damage was estimated at about $1.7 billion (in 2019 dollars).

Allison

With maximum sustained winds of 97 km per hr (60 mph), when Allison moved ashore at the eastern end of Galveston, TX on 5 June 2001 it's sustained winds were only 80 km per hr (50 mph). Yet this weak system produced near-record rainfall and massive flooding from eastern Texas across the Gulf States and along the mid-Atlantic coast. Allison ranks as the most deadly and costly tropical storm ever to strike the U.S. mainland.

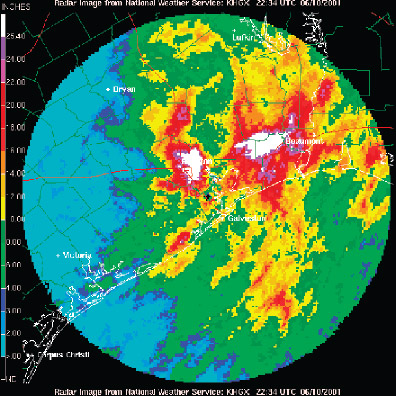

Because of weak steering winds aloft, Allison followed an erratic path from 4-9 June, a meandering counterclockwise loop over eastern Texas that weakened to a tropical depression on 7 June and twice soaking the Houston metropolitan area (Figure 2). During this period, rainfall totals in the Houston area included 94 cm (36.99 in.) at Port of Houston and 90.1 cm (35.67 in.) at Greens Bayou. The system’s remnant circulation then drifted southward into the northwestern Gulf of Mexico, where it intensified into a subtropical cyclone (a weather system with characteristics of both tropical and extratropical cyclones).

Figure 2. Radar-determined cumulative rainfall over southeast Texas (Houston and Galveston near center) produced by the remnants of tropical storm Allison for the period ending on 10 June 2001. [NOAA/NWS]

On 11 June, Allison moved inland over Louisiana where torrential rains totaled 75.8 cm (29.86 in.) at Thibodaux and 70 cm (27.55 in.) at Salt Point. The system slowly drifted over southeastern Mississippi and then northeast to eastern North Carolina, where it again stalled on 14 June. Tallahassee, FL recorded a 24-hr record rainfall of 25.7 cm (10.13 in.) from the 11 to 12. On 17 June, Allison tracked toward the northeast off the mid-Atlantic coast and eventually dissipated on 19 June over the North Atlantic southeast of Nova Scotia.

All told, Allison took the lives of 43 people and caused at least $12 billion (2019 dollars) in property damage.

Irene

Irene was one of the costliest hurricanes to impact the northeast U.S. It evolved from a well-defined tropical wave east of the Lesser Antilles, developing into Tropical Storm Irene on 20 August 2011, and the same day made landfall on St. Croix. A day later, the intensifying, now category 1 hurricane, storm made landfall in Puerto Rico and the Bahamas with maximum intensity as a category 3 with winds peaking at 195 km per hr (120 mph). Irene then curved northward, weakening to a category 1 before making landfall at Cape Lookout just west of the Outer Banks of North Carolina on 27 August (Figure 3). Maximum sustained winds were 140 km per hr (85 mph).

Figure 3. The track of Hurricane Irene in August 2011. [NOAA data]

Gradually weakening as it hugged the coastline tracking north-northeast from southeast Virginia to the Atlantic, Irene made landfall as a tropical storm on the southeast New Jersey shore on 28 August. Irene’s final landfall was near New York City, NY. As it turned northeastward, the storm began developing extratropical characteristics and accelerated into New England, crossing the Vermont-New Hampshire border, then tracking into eastern Quebec and Newfoundland.

Irene was responsible for loss of lives in the Caribbean and U.S. and considerable property damage, mostly due to coastal and inland flooding and severe beach erosion. Total damage in the Caribbean and Canada was estimated at close to $1 billion, and in the U.S. near $15.7 billion (2019 dollars) and there were 45 U.S. fatalities. Storm surge heights included 1.4 m (4.56 ft.) at Sewells Point, VA, and 1.4 m (4.50 ft.) at the Battery in New York City.

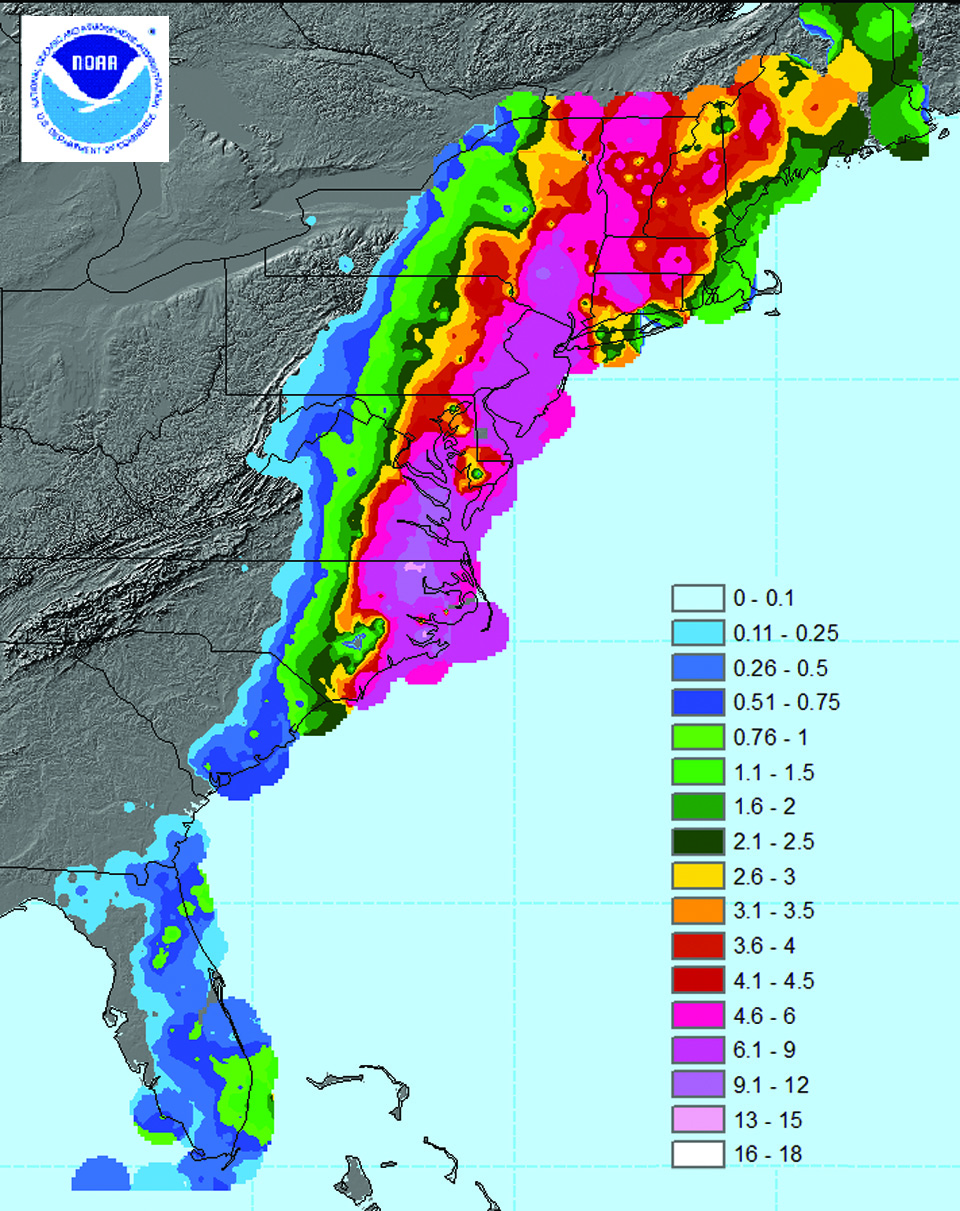

Rainfall was very heavy, with storm totals generally ranging from 13–38 cm (5–15 in.) from eastern North Carolina into parts of New England (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Hurricane Irene preliminary rainfall data (in inches) for 25-29 August 2011. [Courtesy of Michael Kruk, NOAA/NCDC]

Rains falling on already-saturated soils resulted in considerable runoff and record flooding from the northern mid-Atlantic to New England. On 27–28 August, millions of customers were without electricity because of strong winds bringing down tree limbs and power lines. Heavy rains coupled with hilly terrain caused heavy flooding in south and central Vermont that cut off many towns. On 29 August, Otter Creek in Rutland, VT reached 2.8 m (9.21 ft.) above flood stage, breaking the previous record stage of 1.7 m (5.45 ft.) following the 1938 New England hurricane. In New York City, the flood threat closed the subway system and the city’s three major airports, cancelling thousands of flights. Along the coast more than 300,000 people were evacuated from low-lying areas.